“Do not return to work. We have terminated your employment. Do not enter the grounds or we will have you arrested for trespassing.”

This Saturday afternoon, I was under the hood of my 1966 Chevy Impala 396 Super Sport doing some engine work by our barn when Mike pulled into our driveway in his shiny white Ford pickup truck to fire me. I worked at his cheese factory, just a few miles away, six days a week, 12 to 16 hours a day – except Saturday, which was usually a half day. If a reefer truck pulled in and needed loading, we’d be working no matter what day of the week it was.

Mike and his partner, Edgar, owned that cheese factory. When I saw them together, I often smiled to myself a little because they reminded me of a Laurel and Hardy pair. Mike was middle aged and over six feet tall, with broad shoulders and an even broader paunch. Every day, he wore a white dress shirt that never seemed to stay fully tucked in his pants, which had their own difficulty finding where his waist was located. Edgar was much older and a good foot shorter, stooped over and almost frail. His glasses were usually sliding down his nose, probably because the lenses were as thick as the end of a Coke bottle. Neither of the two was particularly cordial or pleasant to deal with. Mike seemed a bit of a bully, his face always on the verge of a snarl, and Edgar walked by you as if you weren’t in the room, on the rare occasions he left his office. Edgar did the books; Mike ran floor operations.

It was just a matter of time before they tried to get rid of me, so I wasn’t surprised at Mike’s news. I kept my mouth shut, nodded once, and turned back to working on my car. Mike backed down the drive and disappeared in a trail of dust kicked up from the dirt road that ran from our farm to the main road. I knew exactly why this happened and how I got here, and I had a plan.

Now in my early 20’s, I was an accidental union organizer. Up until a couple months ago, I’d never given a thought to that calling, and I never did again, though I have a working knowledge of unions and union organizers, from Mother Jones to Joe Hill to Eugene Debs to César Chávez. I also knew a thing or two about labor, growing up on a farm where we breathed work from early morning until late at night. When I was 13 years old, I hired out for the summer to a farmer on the other side of the county six days a week for room and board and $75 a month. My parents picked me up Saturday night and brought me back on Monday morning. This was good money for a kid in those days, and I was so busy working I had nowhere to spend it.

The next two summers I rode my bicycle several miles each day to weed, hoe and plant trees six days a week at a large tree nursery. The following autumns, I spent my weekends picking, grading and selling apples at a neighboring orchard run by an agronomy professor from the University of Minnesota. All the apples you could eat. After school and weekends, I worked maintenance at a restaurant and apartment complex, as a soda jerk at a drug store, and as a prep and line cook at a local restaurant. When I was 17, I graduated from high school, started college and worked between classes and semesters at restaurants, sod fields, gas stations, construction companies and even a destruction company, tearing down old buildings, including the school where I attended first grade as a child. I worked alternating shifts for one summer at a window factory. Graveyard shift was 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. One summer I spent hanging on for dear life on a portable scaffolding high above the ground taking down and putting up billboard advertising. Hot, hard work, particularly in the blazing sun holding a blow torch and burning off the old paper posters. I guess you could call me a poster boy.

Yes, I knew something about work and labor relations.

My goal now was to break the work and school cycle to travel Europe and Africa until whatever money I’d saved for the trip was spent. That’s why I moved from Minneapolis to my grandparents’ farm in Wisconsin to keep expenses low and save every penny I could. I first worked at a feed mill, then took a job at the cheese factory. Terrible pay, even by Wisconsin welfare belt standards, but working 60 to 80 hours a week – no overtime pay – still added up. I also bought cars, fixed them up and resold them at a profit. My trip to Europe was on track.

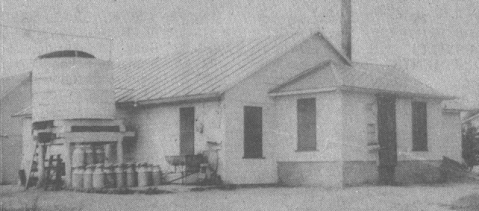

The cheese factory was a dump, an old industrial building with rickety, tacked-on stick additions outfitted with cheese making equipment and storage. It was freezing in the winter and a sweat shop in the summer. We made two cheeses: mozzarella and provolone. The factory bought milk locally and dumped the excess whey in a stream that ran alongside the building. EPA had just been founded a few years earlier, so there was little environmental oversight. Some farmers, including my grandfather, fed it to their hogs. We loaded the cheese on trucks bound for Italian food and pizza factories in Milwaukee and Chicago.

There were two professional cheese makers, but the rest of the work force were people like me – local men and a few women, doing what was necessary, going home at night smelling like whey and brine. We pressed the cheese curds into 12 pound blocks, then moved them from one brine vat to another to age and firm up the cheese quickly. After that, we vacuum packed it with industrial Cryovac machines.

Many of the crew had families, and all were just getting by, one miss-step away from the dole and the welfare roll. You made friends in a place like that, mainly because you could not afford to make enemies. We spent most of our waking day together. There was a small group of young men, some married, some not, who got together on Saturday night, drank beer and bar hopped. That was the high point of the week, and the only entertainment available in that part of Wisconsin. Arnie was my best cheese hound buddy. He was a competition level talker, wiry and tireless. He could drink twice as much beer as I could, and it never showed. Wisconsin boy.

Arnie lived a couple miles the opposite direction from our farm and the cheese factory in a modest mobile home on his father-in-law’s farm. His wife, Betts, was an all-American Wisconsin farm girl. Arnie met her when she was the county 4-H Queen. A sturdy gal, she was bubbly, pretty, and always friendly, with a bright smile. They’d been married about three months, and she was six months pregnant. There may have been a shotgun involved in the wedding arrangements.

It was Arnie and Betts who turned me into a union organizer. Not that they ever knew that, either then or now.

Arnie called me one night.

“Steve, I can’t make it to work tomorrow. Tell Mike that I’ll get hold of him later in the day.”

“What’s up, buddy,” I said. “Anything I can help with?”

“I have to take Betts to the hospital tonight. Something’s not right with the baby. I’ll let you know.”

When I got to work the next morning in the dark at 0600, I passed on the information. Mike grunted something under his breath and walked away. This was the first day I knew of that Arnie had ever missed work since I’d been there. He couldn’t afford to. There was no sick leave, family leave, paid time off – if you didn’t work, you didn’t get paid. And you might get fired.

Arnie stopped by the farm that evening. Betts was back home, and both she and the baby were fine. But the doctor told them that this was likely going to be an eventful pregnancy that would require more trips to the hospital and maybe a longer hospital stay closer to the time of birth. Arnie’s voice was trembling and his hands were trembling.

“I’m not sure how we’re going to do this without going into debt.”

I went in the house and got a couple beers, and we sat out on the porch and talked. Arnie was already in debt. He was my age, and he owed for the mobile home, a new septic he’d just put in, and his economical little Chevy Vega station wagon. Betts’ parents were farmers – they were comfortable, but cash poor, as anyone who’s run a small farm will understand. Arnie’s job paid poorly and provided absolutely no benefits. No paid leave and no medical insurance. Then, as now, private health insurance was costly.

All of us who worked at the cheese factory were in the same spot. Yet, 15 miles away there was another cheese factory where they had those benefits. It was a union shop. They had decent living wages, overtime, holidays and vacation time, retirement benefits, and medical insurance. They also had no job openings. It was considered to be one of the best places in the county to work.

The following day, I got the name of that cheese factory’s union steward and called him to explain the situation.

“I know all about your cheese factory,” he told me. “You’re not the first person to call me.”

He gave me the telephone number of the union’s regional office in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, about an hour and a half away. The International Brotherhood of the Teamsters. That night, the Teamsters representative called me back, and we talked.

“Yea, it’s the same all over,” he said. “First step is that you have to find out if there are enough workers interested in being part of our union. Many don’t because they’re scared of the owner. Ask around, but don’t use work time to discuss it. If you do, they’ll fire you and there’s not much we can do about it. If they vote the union in and they try to fire you, the Teamsters and Wisconsin’s Department of Industry, Labor and Human Relations (DILHR) will sue them, and we’ll win.”

That’s what I did. That Saturday night when we got together for our traditional Wisconsin social event, bar hopping, I brought it up. There was guarded interest. They all knew people who worked at the union cheese factory, and any one of them would have taken a job there instantly. So I told them to ask around, and if there was enough interest, the Teamsters representative would meet with us, answer questions, and if we were ready, set us up for the next step, which was a formal vote under Wisconsin labor laws and guidance.

It didn’t take long to discover that there was overwhelming interest. I arranged for the Teamsters representative to meet with all those interested at the party room at a local bar. Almost the entire work force, about 30 people, showed up. Yes, hell yes – let’s do it!

The Teamsters and the Wisconsin labor office contacted the cheese factory and set up the vote, monitored by all parties.

The results: Yes. Unanimous.

The cheese factory owners: mad as wasps who’d just had their hive knocked down. They were out for blood. When they found out who the instigator was – who the organizer was – it was my blood they were after. That’s when Mike came to my home to fire me.

Big mistake, Mike. Monday morning, I called the Teamsters office and reported what had transpired.

“Sorry to hear that, Steve, but that often happens. Here’s what we’ll do.”

They explained that it was illegal to fire me for organizing union representation, and doubly illegal to come onto my property at my home and do so. I had an excellent work record, was never late for work, and never missed a day. The Teamsters attorney sent a letter to the owners instructing them to immediately reinstate me with full back pay. They were to send me a registered letter and not call me or set foot on my property until I’d formally accepted the reinstatement by return registered mail. If they didn’t, they would be sued. On my part, I was not to have any contact with them until I had received and formally replied to their letter of reinstatement. If a factory representative came on my property, I was to call the sheriff.

Within a couple weeks, my comrades in arms welcomed me back to work. There wasn’t really any hugging; we shook hands and patted each other on the shoulder. From a safe distance. I didn’t have to buy my own beer for several weeks. That’s how it was in Wisconsin back then.

The owners glared daggers at me when I walked by. They watched me from across the brine tubs and looked out their office window when I left work. A couple times, I saw their trucks drive slowly by the house. Then I started seeing occasional, unfamiliar cars driving slowly by. Later, I found out that the owners were suspected of having mob connections in Chicago. The Mozzarella Connection. The Provolone Connection. The Pizza Mob.

Grandpa assured me that his rifles and shotguns were loaded, just in case any intruder should get past the dogs, which was unlikely.

The union was soon in place. Wages gradually increased, daily hours decreased and people had more time with their families, overtime was paid, and everyone had access to inexpensive health insurance. It became a sought-after place to work in this northwestern Wisconsin county, which had large pockets of abject poverty.

Betts did have a difficult pregnancy, but she came through it in good health, as did their baby boy. Last I heard, just before I left the area, they were working on a second baby. Arnie always needed to keep busy doing something, and Betts didn’t seem to object. Arnie was able to spend more time helping his father-in-law on the family farm, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he eventually took it over.

The Teamsters asked me to be the union steward, but I was already busy on my exit plan.

At the end of the year, Theresa and I set out with our Irish Setter “Erin” on a nonstop, 24-hour drive from Wisconsin to New York City in a 1963 Oldsmobile station wagon that one of Theresa’s neighbors in Eau Claire had given us when we told him about the trip. After spending a couple days enjoying Manhattan and Times Square, I gave the car to the valet at the Manhattan Holiday Inn garage on the condition that he drive us the next morning to the New York Port Authority Passenger Ship Terminal in Hell’s Kitchen. We’d booked passage on an Italian ocean liner, the SS Michelangelo, sailing from New York Harbor and bound for Cannes, France. It was the experience of a lifetime to sail down the Hudson River, past the Statue of Liberty on one side and Battery Park on the other, into the Lower Bay, and out through the New York Bight into the Atlantic Ocean.

The end of this story is just the beginning of another. My May 4 post on this blog, “Travels With Erin,” ended almost exactly where the story you’ve just read ends. The next installment will pick up where “Travels with Erin” ends, and I’ll tell you about our extraordinary ocean liner transit – and its cast of characters – from New York City to Cannes, then our journey to Rennes, France, where we bought a purple 1957 Citroën 2CV that we drove from Brittany in Northwestern France through Spain to North Africa and back to Vannes, at the entrance to the beautiful and historic Gulf of Morbihan in southern Brittany.

See you onboard the SS Michelangelo!

Good story Steve. Very well written and interesting from a few point of someone who grew up about the same time. It is a good example of how hard people worked in those days. I also had some hard jobs growing up. In the end I think it helped us through life. I remember many people that the Saturday night coming into town to get groceries was the high light of their week. Those days were so different than today. Now I know what you have been doing with your spare time. Curt

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Curt! I knew you’d “get” this. We both came of age in the same geographic area during the same time. A time that was very different from now.

LikeLike

Looking forward to reading more stories

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Steve – Another wonderful story and such a contrast to the teenagers now.

In 1965 I came back frolm Athens to NYC on the Cristoforo Colombo – what beautiful ships they were and I wonder what happened to them all. I think yours was the ship that transported the Pietà from Rome to NYC for the Worlds Faire.

We had a new VW beetle on board with us and when we arrived in NY, we were held up for quite some time. They had finally busted the infamous Citroën convertible that had a half false gas tank full of heroin! I don’t know how many transatlantic voyages it had made, but it was discovered on our voyage. They had then let the air out of the tires of all the cars in the hold to make sure they were not full of drugs. I remember that gorgeous car being auctioned off some years later- I don’t know if you are a le Carré fan, but I am enjoying his memoir very much, called the Pigeon Tunnel. Good stuff, old Europe and almost as well written as yours!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Christina! The SS Cristoforo Colombo was the sister ship of the SS Andrea Doria, which famously went to the bottom after a collision in the mid-1950’s. The SS Michelangelo was the sister ship of the SS Raffaello. The Michelangelo could top 30 knots under full power, making her a very fast ship. In 1972, Alfred Hitchcock took the Michelangelo to the Cannes Film Festival. Transatlantic passenger service for the two ships ended in the md-70’s, when the Shah of Iran bought them to use as floating barracks. I am most certainly a le Carre fan! I got hooked with The Spy Who Came In From the Cold in the mid-60’s. Terri Gross had an excellent interview with him this week on Fresh Air – he’s now in his mid 80’s. The Legacy of the Spies should be delivered to my mailbox tomorrow! I can’t wait! Meanwhile, my next chapter of Travels with Erin will be our winter crossing on the Michelangel from NYC to Cannes. Stay tuned!

LikeLike

Steve,

All these great stories. Have you kept a journal all these years or do you have a photographic memory? Keep writing my friend. You definitely have a way with words!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Shawn! Being of – so far – sound mind, I do have a good memory. It sometimes seems strange, but I can remember entire conversations from decades ago, even when I can’t find where I put my car keys this morning. It helps a great deal that I have kept journals. Now that we’ve downsized and moved into a smaller house with limited storage space, I have collected all those journals into one area. There are dozens. I even found a notebook of poetry that I wrote in high school! I will confess that these journals are the basis for these stories. We’ve also been going through boxes of photographs – about 15 large boxes – and making sense of the the perhaps 10,000 slides, negatives and photographs that are in them. Thanks for listening in!

LikeLike

I’m a fan of all your stories but this is my favorite Steve because it’s such a classic moment in American history that sadly so few people working today can imagine or comprehend. A time when one guy caring and sharing another’s plight could decide to stick together and make a difference. And when having a loaded shot gun ready on your farm was about standing your ground against all variety of varmints, rather than taking on your perceived enemies in the streets. So satisfying to know people working in common cause can better their lives together. Why do so many Americans think that’s communism?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! It’s a favorite of mine, as well. I went over and over this to be as sure as I could that it reflected the truth of my experience and that it was my genuine voice, given the years between. If I was missing a bit here or there, I mended it in with authenticity. When I was finally ready to hit “publish,” I had tears in my eyes because I realized, now decades later, that there were layers on layers in this saga – and that in the end, good was done; that people are at their roots are OK; and that I had done right by my fellow humans. I was cleansed. I guess that’s why we write!

LikeLike